Kashmir has a rich Sufi heritage, which is enshrined in the ancient tombs and hermitages (or khanqahs) that dot its landscape. Its encounter with Sufism started in the 14th century, when wave upon wave of Sufi theologians from former Mongol and Timurid territories migrated to Kashmir. Historically, six Sufi monastic orders or silsilas have shaped Islamic religious expression here. These are the Kubrawi, Rishi, Noorbakshi, Suhrawardi, Qadri, and Naqshbandi orders. Except for the Rishi order, which evolved locally, building on pre-existing Hindu and Buddhist religious idiom, all five orders originated from Persia.

The stories of the extraordinary, sometimes miraculous, feats of the Sufi theologians are recorded in tazkiras, which are hagiographic literature in Persian extolling the virtues of its subjects. Although composed in the prophetic tradition of the Hadith and the Quran, Sufi literature distinguishes itself by professing an accommodative Islamic ethos. The difference is especially noticeable when it is compared to the literalism associated with modern revivalist movements within Islam.

For instance, a 16th-century collection of treatises by Baba Dawood Khaki, a Sufi master of the Suhrawardi order, voices what historian Muhammad Ashraf Wani calls “latitudinarian views” on issues like veiling (purdah), innovation (bid’ah), vegetarianism, and celibacy. In the literalist tradition of Islam, discussions on these subjects are not encouraged at all, if not explicity forbidden.

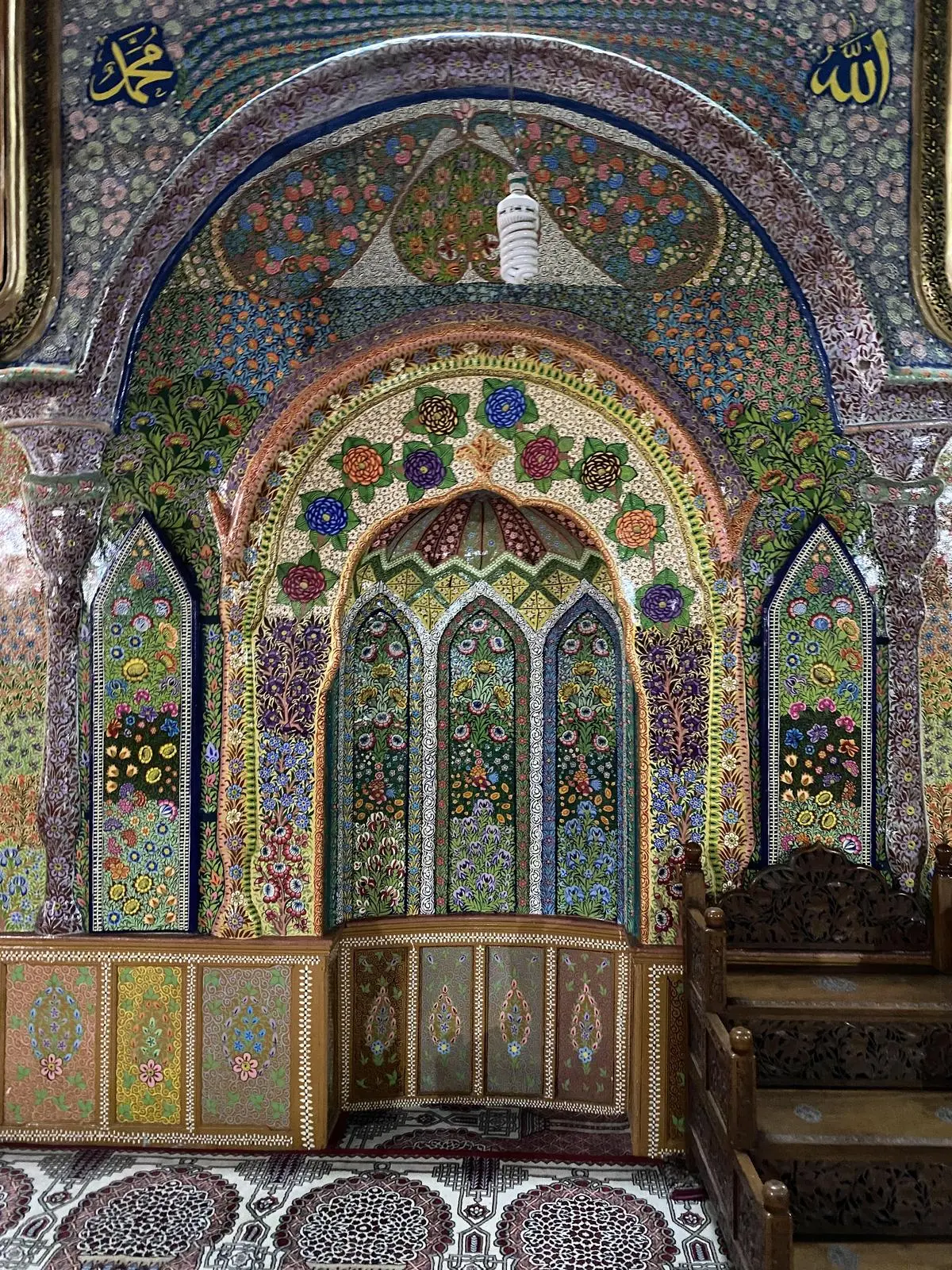

An apsidal recess (mihrab) in the shrine of Shaykh Yaqub Sarfi, the 16th-century poet-theologian of Kashmir. The entire mihrab is embellished with papier-mâché art, which is topped with a coat of lacquer. A popular anecdote gives him the role of an emissary who petitioned Mughal Emperor Akbar to invade Kashmir in the late 16th century.

| Photo Credit:

Shakir Mir

The khanqahs were presided over by Sufi mystics, who prayed in seclusion, performed austere penances, and composed religious treatises. They passed down their knowledge to their pupils, who spread the word through the network of khanqahs that dotted the Valley.

Also Read | Old stones, new tales: How inscriptions rewrite Kashmir’s religious history

“Kashmiri shrines were also sites of culture and innovation. Much of the handicraft and artisanal work for which Kashmir is famous today was probably taught at these Sufi shrines,” said Dean Accardi, historian of gender, religion, and politics in South Asia and the Islamic World, and professor of History at Connecticut College, US.

The five-domed mausoleum where the mother of Zayn-ul-Abidin, a 15th century Kashmiri sultan, is buried. The tomb reflects Timurid influences on Kashmiri architecture. The most unique element are its domes, which have bands of cavetto cornice running round them, followed by a torus line and a fillet with denticulated projections. Each rectangular recess under the cornice is bifurcated by a double band of voussoired arch, giving the dome its Byzantine appearance.

| Photo Credit:

Shakir Mir

The eclecticism of Sufi thought is also reflected in the architecture of the khanqahs, which often display stylistic features of Kashmir’s ancient Hindu temples. The large spires, triangular pediments, corbels, pilasters, and friezes of Sufi shrines are architectural elements associated with temples built during the reigns of Alchon Hun and Karkota rulers, who were Shaivites and Vaishnavites, respectively.

As Islam spread in Kashmir and people converted to the new faith, religious spaces connected to older religions fell into disuse. Many of them were quarried for building material, which was reused in the construction of mosques and shrines. Many structures of Kashmir bear traces of this practice of spolia. The ruins of a Buddhist monastery from the 2nd century CE at Harwan in Srinagar, for example, sit atop the foundations of what was once an Indo-Parthian fire temple.

One of the partially carved stone blocks scattered inside the mosque of Mullah Shah. After Aurangzeb executed Dara Shikoh on August 30, 1695 CE, the construction was halted midway, with carvers reportedly dropping their mallets and chisels on hearing about the sudden demise of their patron. The stones have remained unmoved for more than 300 years.

| Photo Credit:

Shakir Mir

Likewise, when Hinduism became ascendant in Kashmir by the 6th century CE, some Hindu religious spaces were grafted upon the “monastic dwellings of Buddhist priests,” as historian Alexander Cunningham said with reference to the Bumzu cave temple in Anantnag in south Kashmir. In this sense, the khanqahs of Kashmir remain in a state of conversation with, and preserve the cultural zeitgeist of, the region’s past.

In the 19th century, Sufi shrines and mosques became sites for political reform, as historian Mridu Rai has documented in Hindu Rulers, Muslim Subjects: Islam, Rights, and the History of Kashmir (2004).

The original construction of the shrine of Shaykh Abdul Rahim Qadri dates back to 1703 CE. The present structure is unique in the sense that it preserves the old floral designs that are frescoed on its stucco. The high point is the cusped arches of the shrine’s windows decorated with bas-relief work consisting of gold-painted curlicues interlocking into a round cartouche with an acanthus leaf motif.

| Photo Credit:

Shakir Mir

One fascinating case involves the Pathar Masjid in Srinagar. Built during the Mughal rulership of Kashmir in the early 17th century, the mosque was boycotted by local Muslims, who held that it was desecrated by the Mughal Empress Noor Jahan, wife of Emperor Jehangir. Virtually abandoned for more than two centuries, the mosque was revived by Kashmiri Muslim activists in the early 20th century following the decision taken by the ruling Hindu Dogra monarchy (which ruled Jammu and Kashmir till 1947) that it would convert the mosque into an orphanage dedicated to Hanuman.

Also Read | Kashmir’s guarded optimism

The Muslim protests forced the Dogras to abandon their plan. The mosque went on to become the hub of the nascent movement for civil rights that later consolidated itself into the Reading Room Party, which further morphed into the Muslim Conference in 1932, and was renamed as National Conference in 1939—an appellation it retains to this day.

British archaeologist Aurel Stein (1862-1943), in his annotated translation of the Rajatarangini of Kalhana (a 12th-century Sanskrit treatise), identifies these ruins as part of the Raneshwara temple built by Ranaditya, a Hindu king of Kashmir, in 223 CE. Later, Muslim rulers reappropriated the structure as a mosque. There is a Hadith inscription on its stone lintel. The mosque must have fallen into decrepitude when the medieval city of Nawshehra (modern-day Nowshera, a locality in Srinagar), was destroyed in the civil wars.

| Photo Credit:

Shakir Mir

The shrines have other interesting tales associated with them. In the book Resisting Disappearance: Military Occupation and Women’s Activism in Kashmir (2021), anthropologist Ather Zia talks of Zooneh, a Kashmiri woman who travels to almost every shrine in the State to tie votive threads in the belief that her son, Syed Ahmed, allegedly abducted by the Rashtriya Rifles forces at the height of the insurgency in Kashmir during the 1990s, will return one day to untie them.

“In addition to giving spiritual agency, the worship [at the shrines] has also given women a kind of political agency,” Zia said.

Built in 1444, the shrine of Sayyid Muhammad Madni in Srinagar remains out of bounds for worshippers on account of ownership disputes between two religious sects. The Madin Sahib shrine is the only surviving religious space in Kashmir that employs figurative art. The spandrel on its entrance was once decorated with glazed tiles featuring the figure of a centaur with the upper torso of a turbaned archer and with a tail that tapered off into a dragon’s head—a motif representing a synthesis of Persian and Chinese art forms. Some of the tiles were pillaged while others were shifted to the SPS Museum (Shri Pratap Singh Museum) in Srinagar.

| Photo Credit:

Tabish Haider

After 2019, when the Central government revoked the special status granted under Article 370 of the constitution to Jammu and Kashmir, visits to the shrines have acquired a new cultural and spiritual significance, which remains tethered, as always, to the region’s turbulent politics.

A piece of a glazed tile from the Madin Sahib shrine. It is now embedded in the boundary wall of the shrine of Syed Afzal Shah in Srinagar.

| Photo Credit:

Tabish Haider

“As embodiments of Kashmir’s unique culture, the shrines have stoked the interest of the younger generation, who want to understand how their regional and religious identities intersect,” said Muhammad Faysal, curator of Museum of Kashmir, an online archive about Sufi shrines and mystics in the Valley.

This photo essay draws on Persian texts composed in Kashmir between the 15th and 19th centuries to present the unique histories of certain shrines and tombs of Srinagar. The structures open a window to classical Sufi culture, which animates Kashmir to this day.

Shakir Mir is an independent journalist based in Srinagar. His work is located at the intersection of conflict, politics, history, and memory.