Geetanjali Shree’s 1998 novel, Hamara Shahar Us Baras, rendered into English by Daisy Rockwell as Our City That Year (Penguin, 2024), is the story of a communalising city as experienced by a vulnerable narrator grappling with the task of lending language to the self-estrangement of her secular friends. The narrator, who is not a writer but just a scribe, copies hate-filled discourses emanating from an ashram and notes the ease with which “enlightened progressives” start leaning into some version of the “both sides” narrative to come to terms with the situation. No one remains objective or secular. The novel also articulates the thinking person’s confusion in times when people can be either Hindu or Muslim: “Who knows what we were. But whatever we were, perhaps our mother was secular and our father bigoted, and that’s what made us double-headed hydras.”

In the very first short story she published, “Bel Patra” (1989), the International Booker Prize–winning author brought out the insidious way in which communal othering creeps into a mixed couple’s “love” marriage. Shree deals with the theme of communalism in several short stories and the novella Once Elephants lived Here (translated by Daisy Rockwell, coming in 2025) too, showing the various ways—casual and intimate or political and development-oriented—in which our private and public spaces manifest their communal nature. She did a master’s in history from JNU, and the cultural-historic awareness in all her writing is offset by constant self-questioning and examination of the givens.

She firmly focusses on the body, giving primacy to interior spaces and to things that women feel but cannot verbalise. Communalism lurks not just on city streets but also in conversations within four walls, in things that remain unsaid—the silenced tongues, the absent laughs, the unmoving pen—all pointing to the swelling paranoia.

In this insightful interview, Shree tells Frontline how cultivating an awareness of the bewilderment and small violences within and owning up to them helped her arrive at the shape for her recently translated novel. Edited excerpts:

Also Read | Geetanjali Shree writes: The wrestlers’ cause is everybody’s cause

Our City That Year may be telling the story of one year, but to read it is to be caught in time, with a sense of things going round in circles. Can you tell us about this unique treatment of time in the novel?

You are right. The year of the novel does feel like arrested time where things go in circles. There is an oppressive sense of ceaseless repetition. Except that each repetition is more inexorable, more threatening, more dangerous than the preceding one. Maybe it’s more like a vortex of growing velocity.

The dynamic of the subject and the narrative finds itself as one goes along. This novel, too, so found its gait, its tone, its personality. And its treatment of time. The narrative began, as it usually does, with a moment in time. With one particular year. But it soon unfolded that this moment was embedded in the moments that had preceded it. Also, as far as one could see into the future, the moment was unlikely to spend itself in a hurry.

The specificity of Hamara Shahar Us Baras apart, even otherwise I focus on a moment and let it unfurl its details, which constitute both the seemingly unnecessaries and the momentous. Together these meld to produce what a perceptive friend of mine called the palpability of an experience rather than the tangibility of it.

The time span of a novel/literature transcends the immediate. It takes in its sweep the before and after and addresses a continuum. Or else literature will cease to be relevant beyond the absolute present that it is pointing to. This is not by design but because these issues in fact belong to a larger human scale across time and place. Take Anna Karenina, Godaan, Gorky’s Mother, Mahabharata…

Put another way, literature deals with a phenomenon even when it might look at a specific event, and that is why Hamara Shahar Us Baras is not just one city or one year. The problem is far too pervasive, sinister, and sad.

Our City That Year (Penguin, 2024) is the story of a communalising city as experienced by a vulnerable narrator.

| Photo Credit:

By special arrangement

Your novels are not conventionally structured. In Our City That Year, you braid the entire narrative around an inchoate feeling of pressure that the narrator can relieve only by copying everything down. She is also dismissive of her ability to write. What prompted you to fashion such a narrator? Is it indicative of the invisibility a writer must embrace to honestly pursue the solitary task of capturing reality?

You can see this narrator—the anonymous copier—as a metaphor. But as would be clear from my answer to your first question, there was no predesigned general scheme behind it. I do not embrace invisibility. I do not need to. Writing induces a strange kind of erasure. Ustad Ali Akbar Khan, the sarod maestro, has described this phenomenon. I have cited him before. Let me do that again. When he starts, he said, it is him playing the sarod but soon it is the sarod playing him.

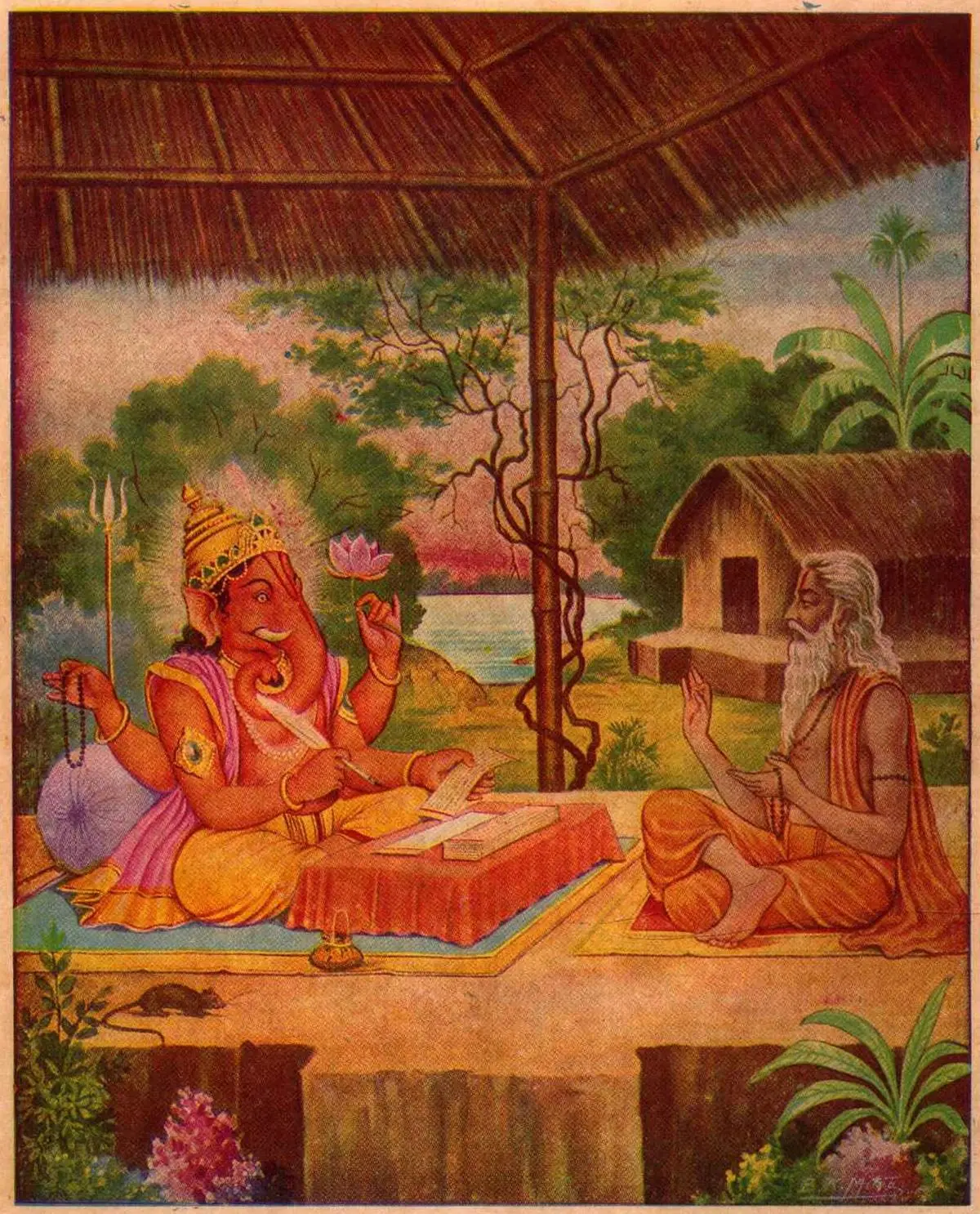

We all know the wonderful story—no matter how apocryphal—about the author-scribe partnership between Vyasa and Ganesh that brought the Mahabharata into being. I suggest this is a beautiful parable about creative writing. Vyasa, the creative force, manifesting itself through Ganesh. In writing. Maybe not all, but many writers would like to see themselves as Ganesh. They are scribes following a larger force. Not mechanically and mindlessly. But like Ganesh, who is under oath to understand what he is asked to write. That is how I see myself. As a writer.

But the narrator in Hamara Shahar Us Baras admits to understanding nothing. I would place her as different from the writer. In fact, she brings in the voice which in doubt, in search, in miscomprehension, in innocence, underscores the urgency of the situation gone out of hand. Hers is a warning and a protest against easy assumptions, laying out anew all that has been presumed to be understood, and demanding that it be rearranged and realigned and rethought. In these times, when too many are overconfident that they know and are full of their certitudes which get neither them nor anybody anywhere, the pressing need is for doubt and questions and always—and always—a condemnation of inhumane ways.

We are plagued by certitudes on all sides. Be they of the fundamentalists, the secularists, or whoever, all certitudes breed arrogance and intolerance and the incapacity to even consider a difference. We are no longer listening. We are concerned only about our own talking. All others be silent. They/we have all failed, and humanity has taken a dip. Which is why we have to figure out everything anew.

“Truth” reveals itself serendipitously, in unexpected glimmers and turns of the corner. So, it is important to go along “unexplored” paths, without fixed agendas, in search, in doubt, in uncertainty. As opposed to going on known ways, along known stops, spouting known “facts”, being certain and sure.

The novel is written in that spirit. The plague of communalism has spread: why, what is adding fuel to the fire, what has gone wrong in the ways of seeing by all sides? The questions and doubts speak of the urgency of the situation, but the novel provides no answers; its purpose is to remind us of the questions we have too readily answered and forgotten.

“Maybe not all, but many writers would like to see themselves as Ganesh. They are scribes following a larger force.” In this illustration from Sankshipta Mahabharat, Part 1 (Gita Press), Vyasa dictates the Mahabharata to Ganesha.

| Photo Credit:

Wiki Commons

Academic studies of incidents incline towards a certainty that seldom exists in real life. Your novel’s narrator is not into theorising or giving lectures but wants to capture the fear, anxiety, uncertainty, and absurdity through her writing. How has reclaiming language/writing helped you in reclaiming agency in times of fear and confusion?

The academic and the novelist may deal with the same subject, but the protocol guiding them is different. The academic endeavours to clarify, explain, and seek closure. The novelist is happy to be confounded, and to confound; to open up new spaces and leave them so. But, in doing what they do, both further understanding.

Agency is never lost—we always devise strategies and languages to exercise it. Inadequately it may be! But even that is a collective going somewhere.

When I first read the novel in Hindi, the scenes and dialogues among departmental colleagues stunned me because in recent years we have heard iterations of similar words and dialogues all around us. You show how individuals in institutions align with reigning politics so that objectivity becomes a ruse and a shield. Was this awareness part of why you chose the discomfort of literature over the comfort of academia?

The last point first—for me academia is discomfort and writing a comfort! Because it permits me to express being lost and floundering in a way that academics wouldn’t. Because it allows me to express the incomplete and the inchoate in a way that academics will not.

No place is hermetically sealed. The less so in today’s globalised world. Much of my writing plays out in the home because that supposedly closed, protected space is a microcosm of the wider world. The binaries of the home and the world, the outside and the inside, the political and the personal don’t take us very far. Every space gets invaded with currents from outside that space. University departments, no less.

“Recent years”, you say. This recent has been going on for longer than recently!

“My language is my homeland, motherland, my memory, and my protest too. I have inherited it, but I also reconstruct it.”

Also Read | Writing Partition: A violent birth

You use language rich in sound and rhythm words; they add not just pungency and power but also become a constituent of the narrative. In this novel, you put laughter and terror, paranoia and poetry together, forming patterns like ripples in a pond. What can you tell us about this deployment of language as narrative consciousness?

Over the years, in my journey as a writer, one of the most profound things I have learnt is that language is no mere tool to be used as a mere vehicle to convey and carry ideas. It is in itself an entity and has its own personality and must not be used just utilitarianly. My language is my homeland, motherland, my memory, and my protest too. I have inherited it, but I also reconstruct it. In that sense, language is a statement. In this novel it represents the pluralism which is my home and also asserts that as the value I will not let go.

Apart from rigorous self-examination, what would you say is the key to bridging the communal divide?

Meaningful self-examination implies an understanding—a world-view—that takes for granted the existence of others. It accepts as axiomatic genuine respect for those you see as different from yourself. One will need to say a great deal about bridging the communal divide in general. But, thankfully, you’ve asked only about the key to doing this.

I am no seer and can hardly proffer such wisdom. But it is about my country which is my home. So I try. The communal problem has got badly entangled in all these years. It is imperative, but not easy, to untangle it. The important thing is to begin now and not in a yesterday. The past is to learn from, not to attack from.

Rooted as it is in the past, the problem has its history. This history is, more often than not, seen in rival, unselfconsciously partisan terms. It is very hard to be rid of the prejudices that sustain partisanships. Aiming to be completely rid of them may be unrealistic. But it should be realistic to recognise, pragmatically, that whatever the wrongs of the past, endless settling of scores will settle nothing. It is in everyone’s interest to let go of past wrongs and concentrate on the well-being of all now. This calls for good faith. Conversations among all parties. Comradely proximities. Dignity of all. Eschewing of violence.

When is your next novel out? What is it about?

When I decide to hand it to the publisher. It is ready. I prefer not to talk about a work not yet out in the readers’ domain, but generally speaking, it is about the ephemerality of love and life, of missing the moments of connect, and valuing love and life when it’s lost. For the moment I can only tell you that it is titled Sah-sa.

Varsha Tiwary is a Delhi-based writer and translator. She recently published 1990, Aramganj, a translation of the bestselling Hindi novel Rambhakt Rangbaz.