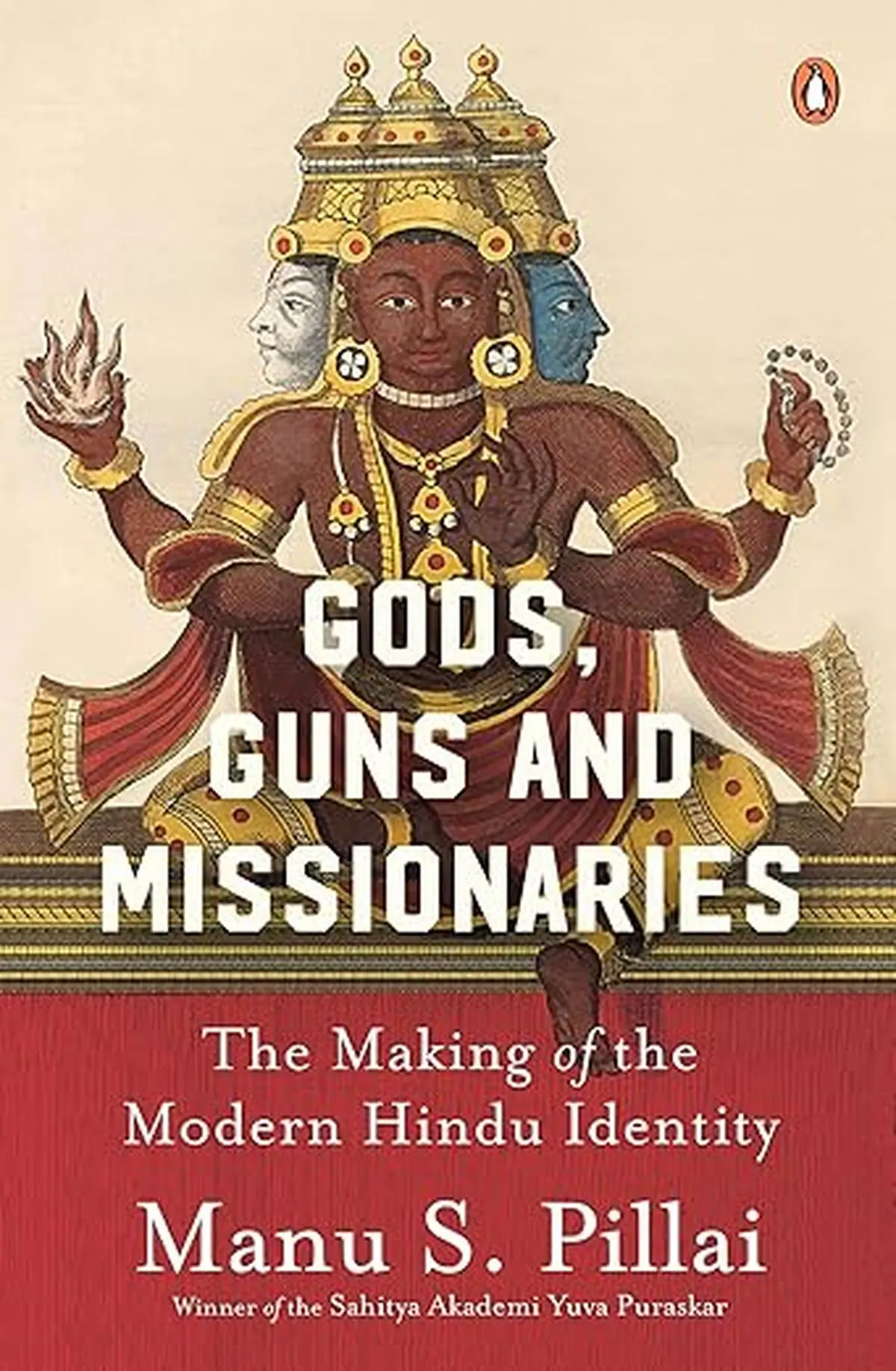

Magisterial in its sweep, Manu S. Pillai’s Gods, Guns and Missionaries: The Making of The Modern Hindu Identity journeys through 400 years of colonial rule, examining how India’s encounter with Europe catalysed shifts in Hinduism, in theory and practice. Scrupulously researched and narrated with an authoritative ease, the book explores the way Hindus responded to the challenges posed by colonial rule and missionary activity—a complex, negotiated process that demanded adaptations and makeovers on the one hand, and resistance and pushback on the other.

Gods, Guns and Missionaries is a courageous work that privileges fact over political correctness and prejudice. Pillai demonstrates that unusual ability to be at once scholarly and extremely readable, peopling his book with an array of fascinating characters and supporting his arguments with a compelling narrative style. In an interview with Frontline, he talks about his book, the inherent diversity of Hinduism, and his wariness of over-sensitive readers. Edited excerpts:

Hinduism, as you have suggested, is not easy to define. But leaving aside the contingent and historical factors that have shaped Hinduism, and looking to the texts, would it be correct to say that the Puranas—capricious or inconsistent though they may be—have done more towards contributing to a “Hinduness” or a shared sense of identity? And the Ramayana and Mahabharata, as well, of course? If yes, does Hinduism, at the ground level, basically exist in a rich tapestry of stories?

Yes, I would say so. What we now frame as an “ism” is not a Western-style religion of the book but a shared cultural framework. I often use the metaphor of a tapestry that is expanding constantly, drawing in more colour and threads. It allows for room to believe in different kinds of ideas, gods, and philosophies, and yet remain part of that fabric (albeit at “higher” and “lower” levels, with its internal politics). The Puranas and the epics were integral to creating this shared system. And stories are central to Hinduism, even if sometimes they get lampooned—gods becoming relatives through marriage, or local deities being co-opted as “forms” of pan-Indian gods via specially crafted origin myths. In fact, there were even attempts to draw Islam into the Puranic framework, with one tale showing Siva blessing Prophet Muhammad.

However, faced with frameworks introduced by sternly monotheistic religions—a different style of conceptualising faith and identity—there was also, from the mediaeval period, an impulse to stitch up that tapestry’s borders. To close the door, as it were. This impulse grew sharper in the modern period, in the encounter with European colonialism, producing Hindu-ism as we envision it today. Yet, this is only how Hinduism self-represents when faced with Others; on the ground it remains a rich, diverse phenomenon, continuing to defy easy definition.

Gods, Guns and Missionaries journeys through 400 years of colonial rule, examining how India’s encounter with Europe catalysed shifts in Hinduism.

| Photo Credit:

By special arrangement

Also Read | ‘Vivekananda is the ideological nemesis of the Sangh Parivar’: Govind Krishnan V.

European attitudes to Hinduism over the years ranged from prejudice and revulsion to making a serious attempt to understand it, even to try find its (elusive) core. Hindu pluralism may have made it difficult to provide a unified theological defence against Christianity. But was it not this very pluralism that allowed Hinduism to absorb, reinterpret and reform in the face of external challenges? Didn’t pluralism provide a handle for Hinduism’s resistance and survival?

Very much. Precisely because Hinduism is a composite of many traditions, its religious archive contains diverse, even contradictory strands of thought. There are monotheistic ideas sitting alongside polytheistic practices, for instance. So, when Western figures ridiculed the latter, Hindus could stress the former, asserting parity with their rivals. Hinduism’s pluralism was exactly why, if under attack for one set of practices or beliefs from missionaries, it could shield itself by deploying a different fount of tradition. It has this unusual capacity to wear multiple faces, and of shifting shapes according to context. All this stems from its pluralism.

What is a bit worrying is that colonial political pressures along with the rise of nationalism led to a tendency towards regimentation. This also birthed, where Hindu nationalism is concerned, a drive for homogenisation. And homogeneity is alien to Hinduism. It has, through all its centuries of evolution, made room, one way or the other, for the many. It is one in its broader framework, yes, but full of variety within. To lose that inner diversity would be, in my opinion, tragic. Yet it is happening all around us, as a continuing reaction to what colonialism and modernity set off in India. Aspects of the past in a sense haunt our present.

There was a stark difference between the Portuguese, who married mercantilism with an aggressive, even violent, missionary zeal, and the British, who were more pragmatic when dealing with the Hindu faith. Was this because the Portuguese arrived in Goa at a more riven and angry time? The Portuguese Inquisition, after all, followed not long after Albuquerque captured Goa in the early 16th century.

One thing we must always examine when studying colonial interactions with “native” cultures is the dynamics at home, in Europe, of the colonising powers. At first, the Portuguese in Goa were accommodative of local religions. Aggression was triggered in great measure by changes at home. For instance, the Catholic church was under attack from the emerging Protestant movement. Protestants accused Catholics of “idolatry” and other assorted sins. Partly to demonstrate their own bona fide Christian credentials, and to take some of the sting out of the Protestant attack, the Catholic regime in Goa began persecuting Hindus in India as “idolaters”. Hindus were the Other against whom their own Christian identity was reinforced, when that identity was besieged in Europe.

Even with the British, at first there was a desire not to get mixed up in religion. Into the 19th century this changed, due to dynamics in Britain—the growth of an evangelical movement, partly as a reaction to the so-called rationalistic Enlightenment; the industrial revolution and resultant social convulsions, which triggered a new religiosity; and so on. This placed pressure on the Company to act like a Christian power. So where British officers earlier had no problems smashing coconuts, attending Hindu ceremonies, and donating to temples, now there was withdrawal and contempt. To understand colonial attitudes in India, that is, we must also analyse simultaneous processes in Europe.

The banner of the Spanish Inquisition in Goa. Engraving by B. Picart, 1722.

| Photo Credit:

Wellcome Library, London/ Wiki Commons

Besides the evangelical surge in the early 19th century, did the fact that Britain and the Company wielded much more power in India, and therefore needed to be less sensitive about issues such as conversion and more forthright in asserting the Christian faith, play a role?

Yes, there was certainly a rise in imperialistic thinking by the 19th century. Company leaders were increasingly from the aristocracy and entered India with yearnings of glory and empire-building. There was also a desire to compensate for embarrassments elsewhere—for instance, the loss of America. But it was never the case that the Company spoke as one voice. Directors in London were typically opposed to conquest; except that sitting far away they could not control military-minded men on the ground. Even among the men in India, some argued for staying in the good books of “natives” while others showed a racist dismissal of “native” culture.

But yes, by the middle of the century there was definitely a sense, among Indians at any rate, that the Company was arrogant; that it was flouting treaties and acting unjustly towards Indian rulers (who were also cultural icons); and that it was promoting Christianity in India. Lord Dalhousie, for instance, had very strong evangelical sympathies. And to Hindus it looked like this was influencing government policy.

Lord Dalhousie had very strong evangelical sympathies. Here is his portrait from 1847 by John Watson-Gordon.

| Photo Credit:

Wiki Commons

Also Read | Nandini Das: ‘Sense of uncertainty haunted the English in Mughal India’

Most of the book is spent on detailing Hinduism’s response and resistance to the Christian West. But didn’t Islam have a great impact as well? Organisations such as the Hindu Mahasabha and the RSS were born largely in response to what they believed, or claimed, was the growing influence of Muslim fundamentalism.

Islam did have an impact. In fact, in the Introduction, I refer to the fact that awareness of a shared “Hinduness” initially emerged under Islamic rule. Faced with an Other—of a different cultural origin, not easy to absorb into the Puranic universe, and backed by autonomous power—Hindus did grow defensive. So, the roots of what we now call communalism do not lie in the British period. The British certainly exacerbated and exploited Hindu-Muslim differences, but evidence of such differences already existed in the works of Kabir, Eknath, Vidyapati etc. But this subject requires a separate book. Not the least because Indian Islam had its own responses and reaction to Western colonialism. Just as Hindus debated missionaries in public, so did Muslim clerics. It is a fascinating story, which deserves separate, sustained investigation.

One of the many striking things that emerges while reading your book is that we lived—for at least four centuries—in a time when religions and religious beliefs were criticised, and very severely at that. Much of what was said in that time, by people of all faiths, would be regarded as “religious insult”, and fall under the purview of the infamous and much misused Section 295 of the Indian Penal Code (or today, Section 299 of the Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita). The British may have wielded great political power, but there existed something that resembled J.S. Mill’s “marketplace of ideas”. Would you agree that people get religiously offended much too easily nowadays?

Certainly. With this book, for the first time in my life, my manuscript went through a “legal read”. I understand my publisher’s caution, because we live in a kind of pressure cooker at present. Yet it is also amusing. Reading the writings of Jyotiba Phule, for example, one cannot help but wonder if he could have written today all that he did in the 19th century. So also Dayananda Saraswati and Rammohan Roy—they would all have been hauled over the coals, or worse, for their writings had they lived in a climate similar to ours.

But I think it is also technology: in their time, these writings remained confined to certain classes and people. Today, with social media, the Internet, misinformation, etc., things travel fast and reach audiences for whom they are not intended. Roy and co. had critics, yes, but luckily they were spared the online trolls.

The likes of Rammohan Roy had their critics but luckily they were spared the online trolls. Roy’s portrait here shows him in London. By Rembrandt Peale

| Photo Credit:

Wiki Commons

In this frenzied, social media-driven environment where nuance and granularity are sacrificed at the altar of polarised, fossilised ideological blocs, do you think a book like yours, rich in detail and unafraid of relating uncomfortable facts, runs the risk of displeasing both the left and the right?

This did cross my mind. As I was doing my edits, I could tell which chapters were likely to “annoy” each side. But I am not too worried—I think intelligent readers, whatever their political leanings, will understand the book. Only the stubbornly ideological, for whom anything that challenges their position is rejected, are likely to be displeased. But this type of reader usually reads only a certain kind of self-affirming book. Hopefully they will leave mine alone. I am happy to be ignored by the over-sensitive. But perhaps that is wishful thinking.

Mukund Padmanabhan is a Distinguished Professor of Philosophy at Krea University and was the former Editor of The Hindu.