Shyam Benegal’s love for films started when he was a child. His appetite for them was voracious. When he couldn’t afford to watch them, he befriended the projectionist of his local cinema and watched them through his window. Sometimes he and his friend wedged the door open a crack so he could see the movie. It wasn’t comfortable but it didn’t matter. Those flickering shadows held him in thrall.

When Benegal grew up, he quickly realised he couldn’t make the films that he wanted to, and so he waited until he could open new windows for himself. And in the process, he changed Indian cinema in fundamental ways.

While researching for my book on him, my publisher sent me his number and asked me request him for an interview. He was busy with post-production work on Mujib: The Making of a Nation, but graciously gave me a couple of days at his office in Tardeo, Mumbai. He patiently answered all my questions for hours.

Benegal was a man of quiet, unassuming erudition. Surrounded by books in his cosy office, he could easily be mistaken for an emeritus professor. After every question, he would pause, collect his thoughts before answering. While talking to him I was struck by a strange paradox: he had dedicated his life to making serious cinema but didn’t take himself or even the medium too seriously. When I asked him about the unavailability of many of his films, he chuckled and said that films are commodities with short lifespans. This strong streak of practicality is perhaps why his films are complex, thought-provoking but never pretentious.

Also Read | Out of focus: Review of ‘ReFocus: The Films of Shyam Benegal’

Benegal’s love for the medium came first. His childhood was spent in Trimulgherry, a cantonment in Secunderabad. It was here that he decided he will be a filmmaker when he was just ten. He found films to be extremely immersive, a form that can transport one into a different world. It evokes immediate visceral responses, like when he witnessed the first jump scare in cinema in Jacques Tourneur’s Cat People in 1942. Later, he made films with strong messages, but he never let it overwhelm the artistry of the medium.

He, in fact, learnt the craft in the most unlikely way. His cousin, Guru Dutt, who had made a name for himself in the industry, had offered him a job as an assistant director. But he refused: he didn’t care much for commercial cinema because it was, at best, a product of compromise or, at worst, escapist fluff of no real value. Instead, he moved to Bombay and joined the National Advertising Agency. He not only made hundreds of ad films but was also asked to take them by road all over the northeast from Jorhat, Assam. His knowledge of advertising distribution networks came in handy when he had to bypass traditional film distribution circuits for his first film.

Intrigued by the form

From his experience of making short ad films, Benegal learnt to effectively compress information into the least number of frames, while simultaneously sustaining the audience’s interest and curiosity. These are commercial skills but also lessons in economical storytelling. His first trilogy of films is characterised by this bare, clinically efficient approach. He always remained intrigued by the form itself.

Benegal was destined to be an artist with strong political views. His family comprised people with widely different beliefs: his father was a firebrand Gandhian, one of his cousins was a communist while another was a member of the RSS. His uncle, Dinkar Rao, his comrade in sneaking out to watch films, had walked all the way to their home from Rangoon when it fell to the Japanese in 1942. Dinkar’s brother was part of the Forward Bloc and was detained at a British prisoner-of-war camp. When he returned, the sight of his broken, disease-ridden body impacted young Shyam greatly.

Later, Benegal studied economics at Nizam’s College, and got involved in the challenges arising out of Hyderabad’s integration into the rest of the country soon after Independence. In these years, he read widely, and his love for world literature would lead eventually to his contributions to Doordarshan’s anthology series Katha Sagar. Here, he Indianised stories by Guy De Maupassant, Anton Chekhov, Saki, O. Henry and Katherine Mansfield.

Benegal grew up in a time of such political and socio-cultural ferment that cinema for him would always serve a serious purpose. Yet, his exposure to a wide variety of ideologies ensured that despite his leftist leanings he never used the medium as propaganda. When I asked him about this conflict between art and the message, he said that it’s impossible to not take a position, but it is possible to strive towards balanced objectivity.

The moment I asked him about being the father of parallel cinema he crossed his arms and smiled dismissively. I don’t like that phrase, he said, and then told me why. It puts films in a box with particular connotations. It’s opposed to popular cinema, and so it must always be serious and slow. He pointed out that he made films for everyone, following a firm conviction that people want to watch films with sensitive, intelligent content as long as it does not preach to them.

Benegal belonged to a generation for whom the decades following Independence were about nation-building. His primary concern as an intellectual and as an artist has been to study how the country has shaped its identity in the years following 1947. He explored this theme by taking on subjects from different parts of the country and delving into its past in order to better understand its present. When I asked him about books that had a formative impact on him, he immediately said that he had read Nehru’s The Discovery of India several times.

Benegal was essentially a Nehruvian in his views and in his vision of the nation. Nowhere is this more apparent than in his most ambitious work he undertook for Doordarshan, the epic 53-episode history of India called Bharat Ek Khoj. Work on the series began in 1985, three years before it aired. He tried to ensure the greatest degree of historical fidelity. He and Nitish Roy built 140 sets, and Benegal claimed that their reconstruction of Harappa and Mohenjo-daro still remains the most authentic depiction of that era. Nehru’s vision informed Benegal’s interpretation of history. Those among us who watched the series as children remember the suave and genteel Roshan Seth as Nehru, introducing each episode to the viewer.

But Benegal wasn’t blind to his idol’s shortcomings. He told me that the biggest problem he faced was Nehru’s conflating North India with the whole nation. Benegal was committed to being as diverse and inclusive as possible and refused to be tied down by monolithic narratives of history. He worked around this problem by choosing Om Puri to introduce episodes that were not part of Nehru’s narrative. His celebration of the nation’s diversity comes across in Yatra, one of his most significant forays into television. The series takes the vast network of train tracks that crisscross the country as an emblem of its unity. The first part of the series was shot on the Himsagar Express that ran from Kanyakumari in the deepest south to Shri Mata Vaishno Devi Katra in northern-most India.

The second part was on the Tripura Express that ran from Jaisalmer in the western end of the country to Guwahati in the east. This cruciform structure allowed Benegal to give the viewers a sense of the country’s baffling diversity in geography and culture. It was extremely challenging to shoot these self-contained stories inside trains, but Benegal and his crew pulled it off with tremendous success.

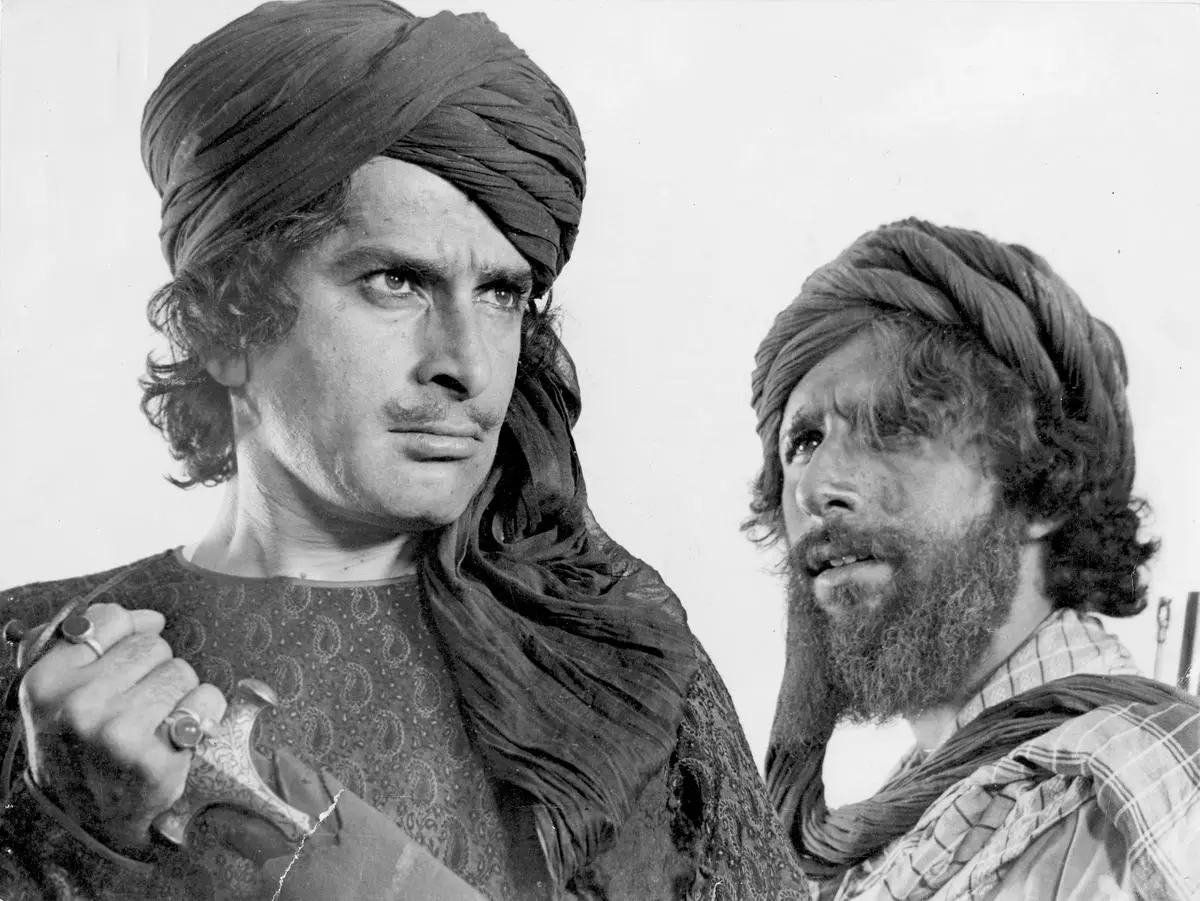

Actors Shashi Kapoor and Naseeruddin Shah in Junoon

| Photo Credit:

THE HINDU ARCHIVES

His complex reading of history is best illustrated in Junoon, his landmark film on the Indian Rebellion of 1857. The film polarised critics and audiences who were expecting a straightforward retelling of the events from an Indian perspective. The film wasn’t about the war itself, which acted more as a catalyst for overturning established social hierarchies, as it was about people who were separated by firmly entrenched social lines brought together in highly charged private spaces. For Benegal, history was about ordinary people caught up in forces larger than them, and in Junoon, the romance between Javed Khan and Ruth Labadoor complicates the simple-minded view of the uprising as an “oppressor vs. oppressed” or “them vs. us” narrative.

In films such as Nishant and Kalyug, Benegal used the Ramayana and the Mahabharata not as religious history but as a reservoir of some foundational values and belief systems. Kalyug replaces the greed for the throne with the greed of capitalism, and begins the film on a factory floor where humans are dwarfed by huge machines, which like sentient giants, carry on the unstoppable business of production. But his treatment of them is not uncritical. In Nishant, Sushila is abducted by a feudal family but she does not passively await rescue; she creates agency for herself in illegitimate spaces.

Benegal’s focus has always been on the individual caught up in networks of largely incomprehensible forces—men and women who are marginalised, exploited, silenced or erased. For him, the only index by which the country’s success after Independence could be measured was its treatment of the dispossessed and the historically disadvantaged. Lakshmi, at the end of Ankur, for instance, screams not just at the cowering landlord’s son but at centuries of systemic injustice and exploitation.

Strong feminist overtones

His third film, Manthan, was meant to be a panegyric to the policies of the party in power, but it doesn’t shy away from pointing out how ostensible triumphs do little to change the position of women in the community. This led him make films with strong feminist overtones. Bhumika uses the backdrop of the film industry to portray how the depiction of women in popular films reinforces gender stereotypes and how women in patriarchal contexts are forced to play subservient roles through their lives.

In 1992, Benegal witnessed the communal riots that broke out after the demolition of the Babri Masjid. He was proactive in trying to restore normality. He made three films about Muslim women caught in webs of history, patriarchal oppression or religious demands. Mahmooda Begum, the protagonist of Mammo, is feisty and boisterous, but her volubility is her only way of asserting an identity in a milieu where she finds herself homeless and constantly pushed to the margins of invisibility. In Sardari Begum and Zubeidaa, we never meet the protagonists; we learn about them through the memories of others. This simple narrative choice gave Benegal a powerful framing device: one that could indicate how a woman’s identity is made up of several narratives, which may have nothing to do with her.

While it is true that cinema was a medium of social reform for Benegal, it’s important to acknowledge his continuing engagement with the form itself. It eventually led to fascinating experimental works that are among his finest films. While his early films were deeply influenced by Italian Neorealist filmmakers such as Vittorio De Sica, he moved away from this bare realism soon after his first trilogy.

An early example of this comes in Bhumika, where he used sepia tints in scenes from the past to convey the unreliability of memory. A subtler departure from his early realism comes in Mandi. Loud, exaggerated and hectic, Benegal drew upon his years in Alyque Padamsee’s theatre to make a farce that used hyperbolic gestures and dialogues. It adopted a theatrical sensibility to make strong socio-political statements about society’s construction of ideas of the acceptable and the illegitimate.

It was however in Trikal that several of his recurrent themes came together to create a profound meditation on the relationship between the past, present, and the future. The film captures the final days of the Portuguese in Goa in 1961 as the Indian Army moves in to annex it. The Suares family (and indeed Goa in general) is caught between a past it romanticises and a future that cannot be denied. Through the film are sudden departures from the real to supernatural encounters, which Benegal uses to draw our attention to more abstract philosophical themes through judicious use of magic realism.

Dismantling grand narratives

Suraj Ka Satvan Ghoda is a postmodern masterpiece that is more about telling stories than about stories reflecting reality. This layered film is about a group of friends who have come to Manik Mulla, the local raconteur and writer to listen to his stories. Benegal, who began his career using cinema as a way of holding up a mirror to reality, now explored how all stories are essentially constructed narratives that can only ever create moments of artificial coherence. In its dismantling of grand narratives, its shifting points of view, unreliable narrators, and artificiality of narratives, Suraj Ka Satvan Ghoda is a remarkably successful work of deconstruction aimed at a largely mainstream audience.

Also Read | Out of focus: Review of ‘ReFocus: The Films of Shyam Benegal’

In the last stage of his career, Benegal moved to a more comic tone in films such as Welcome to Sajjanpur and Well Done Abba. According to him, it was a deliberate choice, because he wanted the audience to laugh along but also ask questions at the end of the film. In these movies, he dealt with the radical socio-cultural and economic changes brought about by liberalisation in the early 1990s. Their light tone is deceptive, because Welcome to Sajjanpur is a shrewd and clever commentary on a town trying to come to terms with changes it cannot fully understand.

There are very few directors in India who have left behind a legacy as important as Benegal. He made it possible for generations of filmmakers to move away from commercial cinema and make films they believed were important. He was a compassionate and judicious critic of the evolving socio-cultural history of post-Independent India. He gave a voice to victims of systemic oppression for centuries and bravely pushed the frontiers of the form.

While he was a man of great humanity and intellect, Benegal wore his achievements lightly. There was always that slightly bemused look on his face, as if he found everything a little funny. Yet for all that, he was a man of iron will who, over the course of a career that spanned 60 years, made films exactly the way he wanted to. And for that, Benegal will remain one of the most important directors this country has ever produced.

Arjun Sengupta teaches English literature at St. Xavier’s College (Autonomous), Kolkata. He takes courses on screenwriting, cinematic adaptations, and media in post-liberalisation India. He is the author of Shyam Benegal: Film-maker of the Real India.